Cemetery of Soviet computers

The building did not stand out. Unremarkable industrial building, which was built in hundreds of Soviet cities.

Non-broken glass, burning lights, live plants inside, modern plastic entrance doors. Except for one floor.

Despite the twilight, the floor remained lifelessly dark. Somewhere in the depths, there was a dim glow of electric light, hardly penetrating through old glass blocks.

Inside the floor was empty and black, but not completely. Inside burned several fluorescent lamps, spotlighting dozens of silhouettes of tall cabinets.

Some of them were covered with darkened translucent film.

The surface of the floor, tables and enclosures covered with black spots of soot, sometimes diluted with white stains of dried extinguishing mixture.

The air felt a persistent, but not strong smell of burning. The fire walked here a few years ago but did not touch the equipment.

Part of the cabinets were antique electronic computers. Others served to measure signals, and computers controlled this process. Dozens of terminals froze on the tables with extinct screens.

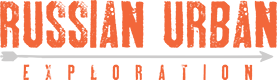

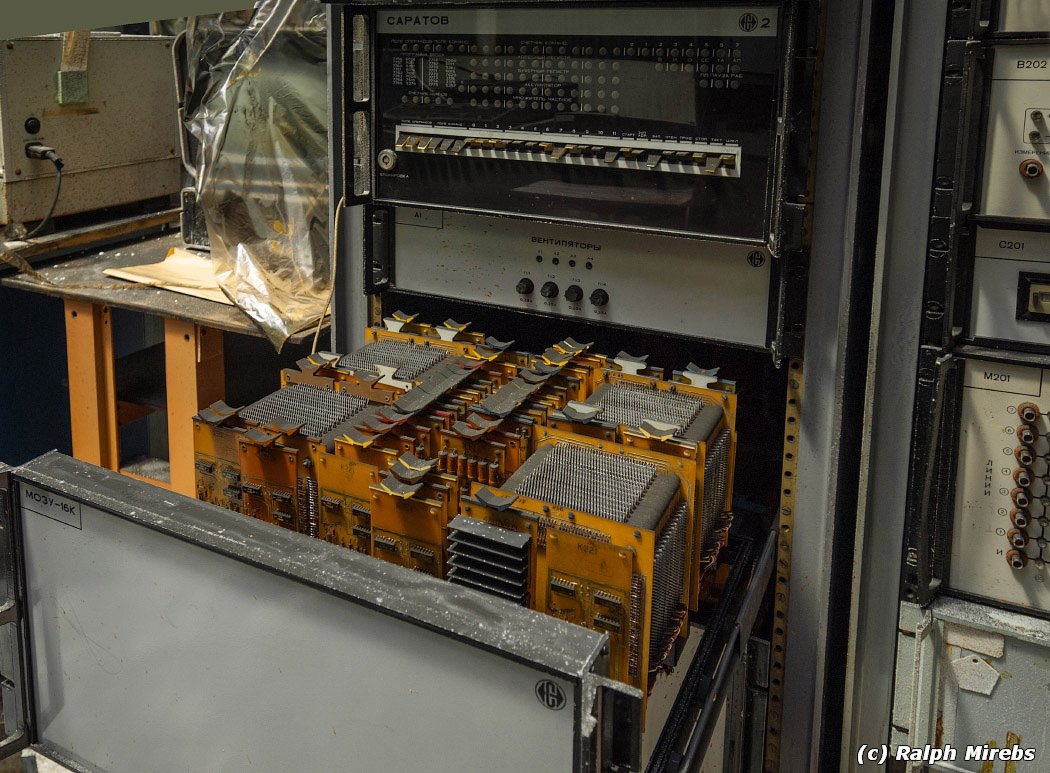

Suddenly it became clear that before them the legendary machine “Saratov-2”. The machine, which was massively placed on many enterprises of the Soviet Union in the 70s, but at the same time, not a single high-quality (I’m not talking about color) photos remained. Not on the Internet, not even in the museum of the enterprise developer.

This computer did not even have a traditional microprocessor. Domestic clone of the popular American PDP-8, Saratov-2 was produced in two versions.

Steel frame, like a chest of drawers, filled with drawers. Different boxes responded to various computer nodes — a twelve-bit computing unit, input-output device interfaces, and RAM.

The memory was ferromagnetic – two boxes of four cubes in each. Reading or writing programs occurred through punched tapes, and to display the results of calculations used electric typewriter CONSUL-260.

The monitor and keyboard in that era were not yet a much-needed

part of the computer. The necessary input of programs into the operative memory was carried out in binary codes, manually using a group of switches on the front panel. Bulbs controlled the correctness of the input.

The next generation of computers was Electronics 100/25. These machines were clones of American PDP-11.

They thought faster, had more memory, allowed them to work with magnetic tape drives and punched tapes, but the general principle remained the same.

It was possible to connect a monitor and a keyboard to this computer, while still having the ability to enter programs through the front switches.

Electronics-60 – the further development of Electronics 100/25. The same architecture, but bulky tape drives are a thing of the past.

They were replaced by flexible eight-inch floppy disks. The new chipset, allowed to fit the processor module, power supply and control devices, in a very compact size.

I note that all these computers were managers, that is, they worked with a bunch of external equipment. It could be machine tools, laboratory complexes, measuring devices.

15VM16-1 some early version of Electronics-60, having a control panel of light bulbs and switches. Assembled on the element base of the previous Electronics 100/25. I occupied a small nightstand built into the table on which the controlled equipment was placed.

DVK-2M or Interactive Computing Complex. Massive, stylish in appearance, the computer of the 80s, which could be considered a personal computer.

It consisted of two desktop blocks – processor and pairing. A set of interchangeable interface cards allowed connecting drives of various types, a monochrome monitor on an openwork leg, and a keyboard.

Back in 1993, when we were studying, one teaching DVK could distribute programs for a couple of dozen Spectrums through the network.

The DVK-3 in the monoblock plastic case is the next stage of the DVK-2M.

3 Comments